ILRF finds labor trafficking and false promises at a “sustainable” palm oil plantation

About the Investigation

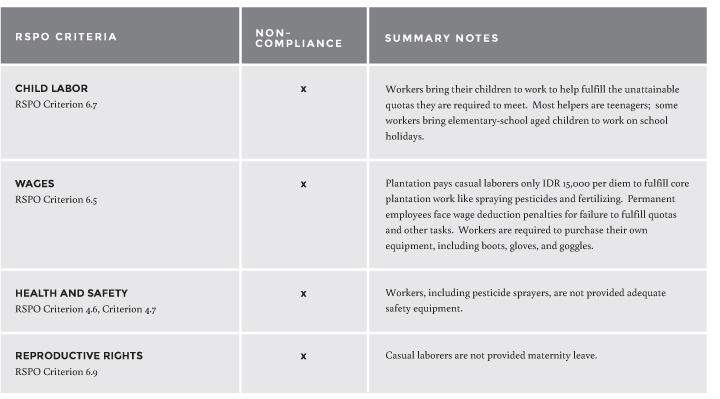

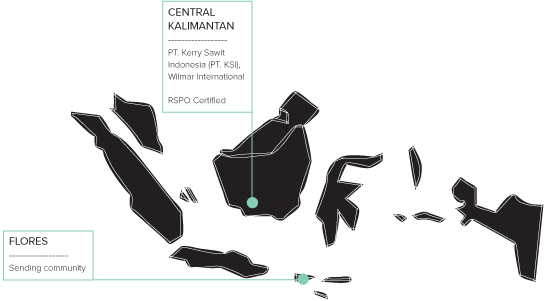

In November 2012, our local field researchers conducted an investigation of the RSPO certified PT Kerry Sawit Indonesia (PT KSI) plantation in remote Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. The assessment primarily consisted of interviews with five workers.

Labor Trafficking: Tomo’s Story

Workers were hesitant to talk to the researchers, but after some trust was built, one man in particular opened up as a group of four others nodded in assent. This 32 year old man was trafficked from Flores with 50 others by a labor recruiter under false promises, and forced by necessity into a debt-bondage-like situation. His story follows.

Attractive Promises

“I was recruited to move from my hometown in Flores to work at this plantation. I have been here now for over a year.

I found out about the job through my uncle Piet Jogo, who is from my village and is now an officer at STPI [the state-run union]. At the time—in July 2011—he was recruiting employees for the plantation. He came to me and told me that a palm oil company was searching for workers.

Back then, I worked for a coconut plantation in my village and madeenough money to meet my basic needs. The recruiter said that if I moved to work for the palm plantation, the company would provide me with everything I needed– even housing, water and electricity. He told me that on top of this I would be paid a monthly salary of 2 million Rupiah [$173 USD/month], or even 3 million [$260 USD/month] if I worked hard. I would be placed either as a fresh fruit bunch harvester or a plantation maintenance worker. He promised that the company would employ my wife as well.

I was very interested in the job from Piet Jogo’s description. Based on what he laid out, I decided to move to Kalimantan with my wife, my three children, and my brother. However, my life here is completely different from what he promised.

The Journey

We only brought 600,000 Rupiah [$52 USD] from home, since we had been promised that all of our needs would be taken care of by the company.

We took a bus for half an hour to Nangaroro, the sub-district capital. Then, we went to Ende by bus for an hour and a half to get to the port.

In total, Piet Jogo recruited 50 of us at once from Flores. We all were on the same ship, which traveled for several days from Ende to Surabaya. From there, we took a ship again to get to Kumai, Pangkalanbuun: another two-night journey.

Piet Jogo provided the shipping ticket, but I had to pay all other transportation costs—including meals for my three children-- despite what he promised. By the time we got to the plantation, we had already been forced to use part of our small 600,000 Rupiah savings.

Once we arrived at Kumai, Pangkalan Bun, we were fetched by a company bus for a final six or seven hour ride. At this point we were divided into two groups: 30 of us were placed at PT SKI and the other 20 were assigned at PT STP.

Necessary Debt

All that Piet Jogo promised came to nothing. We had to survive on our own after we got here. The company provided meals for 3 days, and after that we were left to pay for our own food. Our salary during our three month training was only 200,000 Rupiah ($17 USD), rather than the 2-3 million ($173 - $260 USD) promised. We tried to be as efficient with this money as possible, but it was not enough. We needed to feed ourselves. So we decided to get in debt to the plantation store.

Temporary Employment Status

Once our training ended, we were informed by an administrative assistant that we were to be employed as Permanent Day Laborers. The assistant made the announcement orally, and said that with this status we might get pension insurance.

We never received any employment contract or letter from the company. Since the first day of my employment here, I have not known how much my fixed monthly salary is, or what my benefits are.

Ongoing Conditions

We work extremely hard to harvest the fresh fruit bunches. What we do is not equal to what we receive. I receive 1-2 million Rupiah ($87 - $173 USD) a month. My earnings are not always enough to cover even our daily needs. Everything here is very expensive.2

The company did not employ my wife, but fortunately three months ago she finally found work at PT STP, another palm oil plantation. I am very grateful for this, since often my salary is only enough to pay our monthly debt payment. We owe 1 million Rupiah ($87 USD) a month to the plantation store.

Trapped Away from Home

My life was much better in my home village than here. There was no one forcing me to work so extremely hard, and no burden to pay debts. I want to take my family home, but we are trapped here unless I can earn enough money.

Out of the 30 people who were recruited with me, only six are still here at this plantation. The other 24 have escaped and found work at other palm oil plantations in Hamparan and East Kalimantan. Several of them are working at PT TAS. None that I know of have managed to make their way home. I have heard that their new workplaces are better but a bit hotter. After my experience I personally think that work at any plantation would make a person feel dumbed down, as I have felt since my arrival.

Recruiter Profits

Piet Jogo went home right after we all arrived at the plantation. He never showed up afterwards, or asked about our conditions. On the other hand, I know that he received 50,000 Rupiah ($4.33 USD) from the company for every worker he successfully sent to the plantation. I hate him for what he did to us. He is an irresponsible person. Whenever I meet him in the plantation, I never talk to him.”

--------------------

1 All worker names in this report have been changed to protect identities. The labor recruiter’s name has not been changed. 2 For example, a cup of ramen noodles costs IDR 3,500 at the plantation store if purchased up-front, and if purchased through debt, it costs IDR 4,500 (the worker is charged a one-time fee of IDR 1,000, but no additional interest over time). The same product would cost significantly less in Flores: approximately IDR 2,500.Investigation first published in Empty Assurances, 2013 by ILRF and Sawit Watch